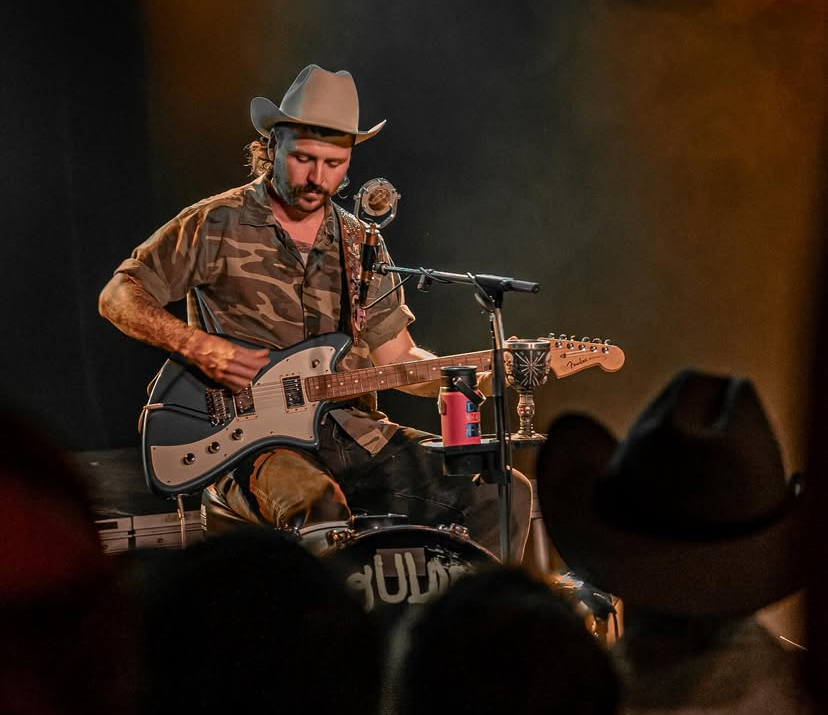

Folk singer Nick Shoulders recently gave his fans an update on the status of his future touring schedule. We reached out to Shoulders to talk about the state of the music industry for independent artists, and how chronic pain has severely affected his ability to stay on the road.

Arkansas

“You’re talking to me from my sunny backyard here in flawless Fayetteville, Arkansas,” Shoulders said as we spoke about his announcement.

Shoulders grew up west of Little Rock “out in the sticks” in Roland before moving into Fayetteville. His father was an ace whistler that learned the skill from his grandpa.

“My folks were athletes,” Shoulders said. “They owned a gym. I had, I think, a lot of musical affinities as a kid, but they were mostly steered by my grandparents. All of them sang. My grandpa actually recorded some really weird, warbly gospel music.”

Grandpa Pat M. Riley, a veteran of the Pacific Theatre, was a Harvard graduate that was raised in Little Rock.

“I’d go and listen to my grandpa sing upstairs from like half way up and make sure he couldn’t see me so I could just kind of absorb it,” Shoulders said.

As his grandparents grew older, his grandmother tragically suffered from dementia.

“I would sit with her and play songs from the 30s and 40s that she could still harmonize on,” Shoulders said.

From Punk Rock to Roots

Shoulders started out as a drummer in punk rock and metal bands while in high school.

“Between songs I would do fiddle tunes on the harmonica and just like stomp on the bass drum,” Shoulders said. “We’d practice in a barn and stuff like that, so it’s not like I could escape things being rural and southern despite the fact that we were playing like scary and screamy music.”

Eventually the traditional folk music he was raised around took a main focus.

“I yodeled in the woods as a kid trying to sound like the owls, and whistled and did all that sort of stuff, played harmonica,” Shoulders said.

In his late teens he started researching traditional banjo and fiddle music from Arkansas.

“I kind of just did that on the side and concentrated on the heavy music as like what I wanted to put out into the world,” Shoulders said.

After touring outside of Arkansas in his early 20s, Shoulders noticed how compelling the traditional music was to audiences, and started composing his own traditional-style works.

“That’s the first time at any point in my life that I’d composed music under my own name,” Shoulders said. “It was kind of a long journey getting there, but it really took being immersed in heavy music and southern DIY to be building the foundational skills of being a musician. The affinity and the connection to old time music, and early country music and folk really came to be something I was composing and putting into the world much later.”

The Big Easy

He decided to move to New Orleans where he immersed himself in songwriting and street performing. Shoulders busked a lot on Royal Street with other working musicians and took spots drumming in night clubs.

“It was kind of this like revolving door of players that all had different styles, different origins, different cultural context that their music came up in,” Shoulders said. “So it was a real delightful mishmash.”

Big Break

At 35, Shoulders has now seen regional and national success, and got his biggest break from Western AF with a live recorded video, but as it was released, the lockdown changed everything.

“All the music work disappeared and that was my full-on livelihood,” Shoulders said. “I was like ‘holy (expletive) the whole damn internet is hearing these songs’ and my life is changing rapidly, and everybody’s lives around me are changing really rapidly with the lockdowns.

I was going from talking to people about record deals, and suddenly aware that people were coming to the shows that we were playing in New Orleans… I went from all that to gathering chickweed in the woods of Arkansas,” Shoulders said. “I thought I was going home for a little vacation.”

Now back in his home state, Shoulders career took a new direction from the tourists filled streets of New Orleans to ticketed events around the region.

“It wasn’t DIY sleeping on couches,” Shoulders said. “It was big boy stuff.”

He said that his love of the outdoors, and the chronic back pain he’s had since his youth have made touring a serious challenge.

“Nature has always been such an anchor for me mentally and emotionally,” Shoulders said. “I’m a kid from the sticks, so I’m actually very, very unhappy in a van, and playing in clubs and bars and being on constant tour, so to balance that I really have this place as a way to heal from tour and a way to bounce back from the road.”

Back home they get to play traditional dances and focus on the historical music in Arkansas. The peace of the Ozarks has kept Shoulders going, but his chronic pain has led to a dramatic change in direction.

Walk It Off

“I grew up in a jock family, so having bodily pain was not ok,” Shoulders said. “If I complained about my back or my legs or just generally not feeling good I was just told to run it off. No shade on my folks, they were doing the best they could with the information they had, but it took me being in those metal bands in my teen years and hauling around giant amps and drums and stuff to suddenly have back problems to the extent that I was laid up, and it was compromising my quality of life.”

At 16, Shoulders’ parents took him to see a chiropractor to have X-Rays and discovered that he was suffering from spondylolisthesis, a condition where the injured vertebra shift or slip forward on the vertebrae directly below it. The doctor explained how the condition had caused his chronic back pain for years.

Soon after the diagnosis, Shoulders then suffered from a collapsed lung.

“That was some pretty intense, invasive surgery,” Shoulders said. “So I had that bodily trauma to deal with also. I spent years living in a van, and riding trains and doing all that dumb stuff so I’ve just like really beaten my body up.”

When it was time to finally tour with backing support of a label, Shoulders’ body was still suffering from chronic pain.

“It compromises my ability to tour nonstop, but I think that is helpful and convenient because this industry really relies on just using people’s bodies up, and mine conveniently was already halfway used up,” Shoulders said. “I get to kind of make my own rules.”

He said that being active can ease the chronic pain, but traveling long distances for shows is the hardest thing to endure.

“It’s fascinating to see how my body really takes to that aspect of things,” Shoulders said. “I can work in the sun all day and really not have too much to complain about, but if you stick me in a van for six hours, then ask me to be a mover and pick up amps and merch, going from static to heavy lifting to then running in place for an hour and a half and then doing the heavy lifting all over again and sleeping in a different bed every night, it really does a number.”

Longevity

Shoulders’ grandparents were able to sing into their 90s, and he said that it’s a goal for him to focus on his longevity and quality of life above his success in the music industry.

“I think I’ve had to be fiercely stubborn about that in ways that I see a lot of performers being uncomfortable,” Shoulders said. “I think all of us are incredibly grateful for the opportunity to do this particular line of work, but without any structures in place, without any workplace protections, without any standards of labor, it’s really up to the stubbornness of the performer to say what their standards of labor are, and a lot of people, for a variety of reasons I think, are compelled to just work themselves to death.”

Shoulders said that booking over a hundred shows a year like he did in the early days is an “impossible gamble.” The foam rollers and other techniques have not provided the relief he needs to run that hard.

“I’ve had times on tour where a sciatica attack made it to where I couldn’t walk for multiple days,” Shoulders said. “I’ve had times where I wake up in the morning and immediately just yelp in pain and can’t move until I have a handful of ibuprofen, and I think I just recognize that this line of work is possible for somebody who’s not totally physically able, it just requires moderation.”

Last year, Shoulders had to tell his band the touring was simply too damaging to his long-term health.

“That paradox of the immovable object of my health, and the unstoppable force of the needs of living in late-stage capitalism has just created this scenario where that’s untenable,” Shoulders said, “so the future going forward is me really concentrating on working smarter and not harder.”

He now takes longer breaks in between shows on tour to protect his back, and a more selective schedule.

“I don’t think you have to reinvent the wheel to be able to do that in this industry,” Shoulders said. “I will be playing less and concentrating more on the quality of life on tour.”

Shorter Runs

Instead of an endless caravan around the country, Shoulders is working with runs of ten to fifteen dates. It’s also freed up his obligations to provide a full time income for a group of fellow artists and industry workers.

The state of the industry, even for what appear to be largely successful artists, is hard to explain to the die hard fans that keep the dreams alive. Simply gassing up the vans, finding a bed to sleep on, and feeding the crew quickly erases the earnings they can rely on back home. While artists like Merle Haggard and Willie Nelson could tour part of the year and rely on album royalties while off the road, the new model sees almost no income for artists from streaming.

Shoulders described the difficult position he was placed in when his friends became his employees, and that many times he felt obligated to continue going even with his back problems.

“Band members contribute mechanically incredibly brilliantly,” Shoulders said. “Like are virtuoso musicians that can add so much to the song, but the songwriting and composition has been my sole responsibility, and as such we can be as avoidant of hierarchy and unfortunate power dynamics as we want to be, but at the end of the day the industry imposes an inherent hierarchy on the situation where the person who’s writing the songs is responsible for so much.”

Shoulders said that watching “friendships transition into a business transaction is tragic, and I feel like so many people would avoid it if they could, but it’s in the DNA and the structure of the music industry as we know it.”

Shoulders just got health insurance last year for the first time in his adult life. The industry itself sees performers and artists as independent contractors without any benefits.

“I am incredibly lucky to get to sing for a living, but until something very fundamentally changes I am firmly on the road for at least fifty to sixty shows a year. That’s about the gamble that I can take where I’m still financially solvent but not dead.”

Gar Hole Records

Back home in Arkansas, Shoulders is paying it forward by funding albums for others with his independent label.

“I’m making a conscious effort to take the success that just fell into my lap, and make sure it benefits my broader community,” Shoulders said.

Right now royalties from streaming can be almost non-existent for most albums, though for professional reasons most will release all of their albums on the major platforms.

“Having access to free music is an unbelievable blessing because you get to build this sonic library, and this basis for your craft that is incredibly valuable, but that shouldn’t take the place of a living wage and health care for musicians,” Shoulders said. “I think if our basic needs could be met without having to resort to being in constant battle with these entrenched forces of corporate capital then we would be a lot happier to have our music available for free.”

As the cost of living is rising, being seen as an artist instead of a performer is not providing the care musicians need to keep going.

“I really feel like if artists were treated as athletes, as performers, as people who deserve the dignity of workplace protections because we do hard physical labor, that the whole climate of how music is treated would be much, much different,” Shoulders said. “We work brutal, long hard days and our reward is just getting to not work for a couple weeks after we just put in 24 hours a day of being stranded from home, and family and a decent quality of life.”

Support the Artist

More information about Nick Shoulders can be found here.

Support Gar Hole Records here.

Photos provided by Robert Kipness.

Support the artist by streaming and purchasing Apocalypse Never on Bandcamp.

Subscribe with your email below for your Song of the Day.

Leave a comment