Presenting the second edition of Love and Theft from Comal County, Texas. Our columnist Robert L. Kelly, the Wolf Cub that performs all over the Hill Country, offers his unique perspective on our rich music history.

“The idea behind this column is to examine how Love can lead to Theft,” Kelly said. “Imitation is, after all, the highest form of flattery, and when we love a work of art, we can’t help but take a piece of it forward with ourselves into our own works.

No harm is meant, and this column is not about accusing anybody of anything, rather it is an exploration and appreciation of the ancient and sacred bonds that link the first caveman to hum to himself while clapping his hands to the musical superstars of tomorrow and beyond.”

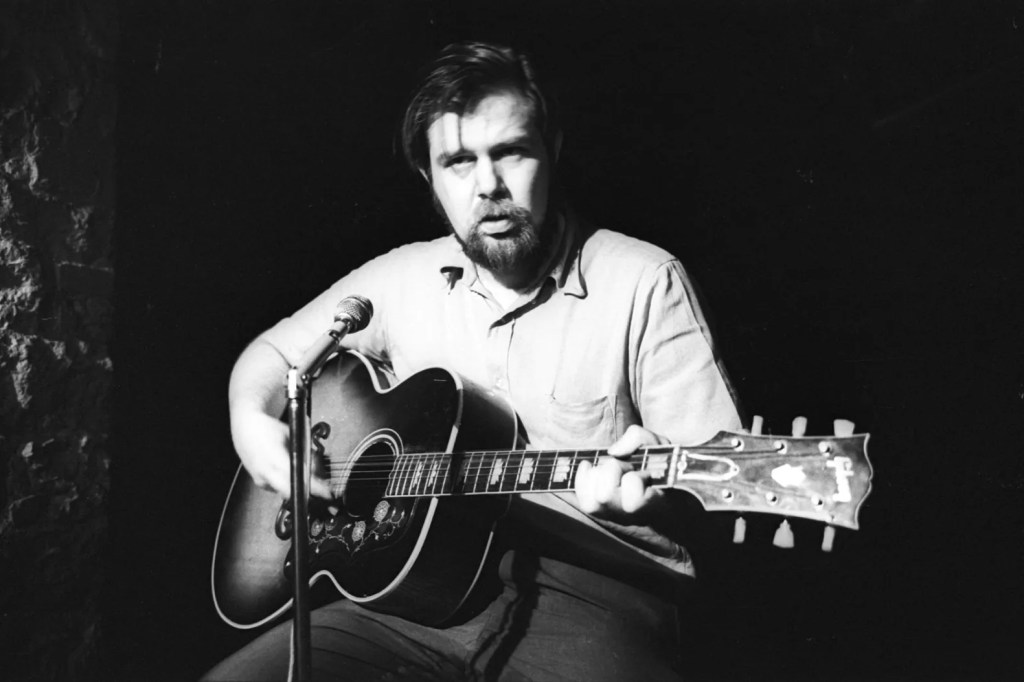

The Mayor of MacDougal Street and the Herky-Jerky Cornfield Refugee

The Mayor of MacDougal Street is essential reading, in my opinion, for anyone interested in American folk music. It’s the memoir of one of the Folk Revival’s most important figures. Outside of a very specific set of music nerds, Dave Van Ronk may not be a household name, but he has had a truly outsized influence on traditional American music. The story I hope to tell today is just one, though probably the best known. I will be quoting liberally from that aforementioned text, and even outside of this yarn the whole thing is worth a read. However, since the crux of this edition of Love and Theft hinges on the relationship between Van Ronk and Bob Dylan, I’ll let the Nobel Prize winner make the introductions. From Dylan’s 2004 memoir Chronicles Volume One:

“He was passionate and stinging, sang like a soldier of fortune and paid the price. Van Ronk could howl and whisper, turn blues into ballads and ballads into blues… in Greenwich Village, Van Ronk was king, and he reigned supreme.”

For his part, Van Ronk has a very different perspective on his meeting the future “voice of a generation”, who he first saw backing up their mutual friend Fred Neil at the Cafe Wha?:

“Fred was up there on stage with his guitar and up there with him, playing harmonica, was the scruffiest-looking refugee from a cornfield I do believe I had ever seen. ‘Where’d he pick up that style of harp blowing? Mars?’”

He goes on to describe Dylan as being full of nervous energy, “herky-jerky, jiggling, sitting on the edge of his chair” and being “just a kid with an abrasive voice. Sam Hood, who took over the Gaslight (Cafe) around that time, insists that he would only use Bobby on crowded nights when he wanted to clear the house.”

In 1962, Bob Dylan released his first album. Self-titled, it featured 13 songs, two of which were original Dylan compositions. The rest were traditional songs or folk revival and blues standards. Among them was “House of the Rising Sun”, which has no writing credit on either the album’s label or jacket, but the liner notes do mention “Dylan learned the song from the singing of Dave Van Ronk: ‘I’d always known Risin’ Sun, but never really knew I knew it until I heard Dave sing it.’”

The two men had a bit of a dust up over this. According to Van Ronk, Dylan asked for permission to record his arrangement after already having completed the sessions that would make up the album.

“I flew into a Donald Duck rage, and I fear I may have said something unkind that could be heard over in Chelsea,” Ronk said.

It’s hard to imagine at this late date, House of the Rising Sun sounding any different from the common version defined in the popular culture by the Animals’ 1964 recording of the song, but in it’s long history, there is very little precedent for the jazz inspired chord progression and bluesy vocal phrasing most performers will adopt when they try their hand at it.

There is a House in New Orleans…

“House of the Rising Sun” is one of many popular American folk songs that tie back to traditional British ballads. In particular, most musicologists I’m aware of note it’s shared history with “St. James Infirmary Blues” and “Streets of Laredo” as variations on “The Unfortunate Rake”, a late 18th century broadside ballad. The earliest published lyrics for “Rising Sun” appeared in a column in Adventure Magazine called “Old Songs That Men Have Sung” in 1925. I’ve attempted to produce the full original text of the lyrics, but publicly available archive materials have let me down. I would like to thank my friend Nathanael Smith for his assistance in digging through said archives, though.

It was first recorded eight years later by Clarence “Tom” Ashley, who taught it to his self described apprentice Roy Acuff.

Acuff released his own version in 1938. From here, it was performed by Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, Josh White, white torch singer and activist Libby Holman (accompanied by White), and Pete Seeger, who is widely considered to have brought it to the New York Folk Revival scene.

Notably, these recordings share an arrangement and chord progression that resembles the Lead Belly song “In the Pines”, E, A, G, B, A, E, creating an unsettling dissonance while remaining in a major key. Josh White’s chord progression flirts with a minor key, but seems to be played with major chords, leaning heavily into his roots as a blues performer. Pete Seeger’s follows suit, despite being played on the banjo.

It’s not until Joan Baez’s 1960 version that we have a version that is truly played in a minor key, and indeed, it’s very near to the familiar progression used by the Animals four years later.

Baez even plays it as an arpeggio, which is a defining aspect of the Animals’ rendition. However, the resolution of her chord progression feels incomplete if you’re more familiar with the later version.

Dave Van Ronk Does Dave Van Ronk Things

It isn’t until Dave Van Ronk that we get the iconic chord chart moving from A minor, C, D, and F back to A minor before resolving through C again, on to E, and then back to A minor. He describes this in his book:

“I put my own spin on it by altering the chords and using a bassline that descended in half-steps- a common enough progression in jazz, but unusual among folksingers.”

Van Ronk had begun his musical career playing tenor banjo in a dixieland jazz band, which called themselves The Brute Force Jazz Band. “We thought that was very witty; audiences thought it was very accurate.” Elsewhere, he reflects, “I wanted to play jazz in the worst way, and I did!”

These roots are reflected both in song choices such as “God Bless the Child”, “Mack the Knife”, “Swingin’ on a Star” across his whole career, as well as his own arrangements of folk standards, like “John Henry” and Woody Guthrie’s “Pastures of’ Plenty”.

“House of the Rising Sun” became a signature song for him in the early sixties, until Dylan’s album began to circulate. At first, Van Ronk was actually not worried about Dylan’s version eclipsing his since, as he put it, “Bobby’s reading had all the subtlety of a Neanderthal with a stone hand ax.” Then people began to ask him to play “That Dylan song about New Orleans.” He dropped it from his repertoire for nearly thirty years.

The story goes that Eric Bourdon and the Animals elected to cover “Rising Sun” when they were opening for Chuck Berry while he was touring the UK in 1964.

Van Ronk’s reaction to Dylan’s loving theft had been passionate and fiery, resolving only when their mutual friends forced them to apologize to each other, he wanted to sue the British band for copyright infringement. After coldly researching legal actions, he discovered that “it is impossible to defend the copyright on an arrangement. Wormwood and gall.” He took some solace in the petty comfort of knowing that Dylan was forced to drop the song from his repertoire due to the popularity of the Animals’ recording.

What it’s All About

With all of the history around the song, it feels a little small-minded to be narrowly focussed on Dave Van Ronk’s relationship to “House of the Rising Sun”. However it’s arguable that he has had a greater impact on the song and hence popular culture than anyone else. Perhaps it’s recency bias, but we live in the time we live in, and hear the Animal’s version in movies and on the radio to the point that it’s become almost a nuisance.

Thanks to Van Ronk’s unique background with traditional jazz music and influence over Bob Dylan and the Folk Revival of the 1960s, we got the version of the song most familiar to the public. Dave Van Ronk is, I think, an unsung hero of American popular music. His biggest moment in the broader popular culture probably came from the Coen Brothers’ 2013 film Inside Llewyn Davis, which borrows heavily from Mayor of MacDougal Street, but paints a much bleaker picture than the one found in the memoir, while portraying the title character as a bitter, unlikeable loser with a lot of talent. While an excellent movie, it’s a disservice to the man who inspired it.

The real Dave Van Ronk gave us what turned out to be a defining piece of the 20th century’s musical legacy, while also providing room, board, and inspiration to a future Nobel Laureate who would come to exemplify the movement to which they both belonged. He was an anchor and the ship all in one. Yet, somehow, I don’t think he’d do more than shrug and maybe shake his head before moving on when looking at his legacy. His memoir was unfinished when he died in 2002, but the ending it got says it pretty well anyway:

“I wanted to be a musician, and I am a musician, and that’s what it’s all about.”

Support the Artist

Love and Theft is a monthly column by Robert L. Kelly.

Subscribe with your email below for your latest story.

Leave a comment